Carving out a new destiny: Dayton’s bid to lift itself up

In August, Netflix released American Factory, a documentary produced by Barack and Michelle Obama that delivers a compelling story about Chinese and American workers brought together in a U.S. factory. It’s an interesting take on the post-recession-underdog American factory worker featured on many an evening news extended report. I’ve never taken in a similar exposé as interesting as this version. In it, Americans have to give ground on their home factory turf not only to a new boss (often referred to as “the chairman”) from a little-understood country, but to then be locked into a daily ideological and temperamental struggle with hundreds of workers from the same world. One feature in particular that made the film a must-see for me is that it takes place in Dayton, Ohio — a part of the U.S. that until this year I wasn’t destined to lay eyes on.

That the Fuyao Glass America story takes place in Dayton is a forceful reminder

for me of all the good that has passed, and that the relative wages and aspirations

of NCR-era Dayton will be wickedly difficult to claw back.

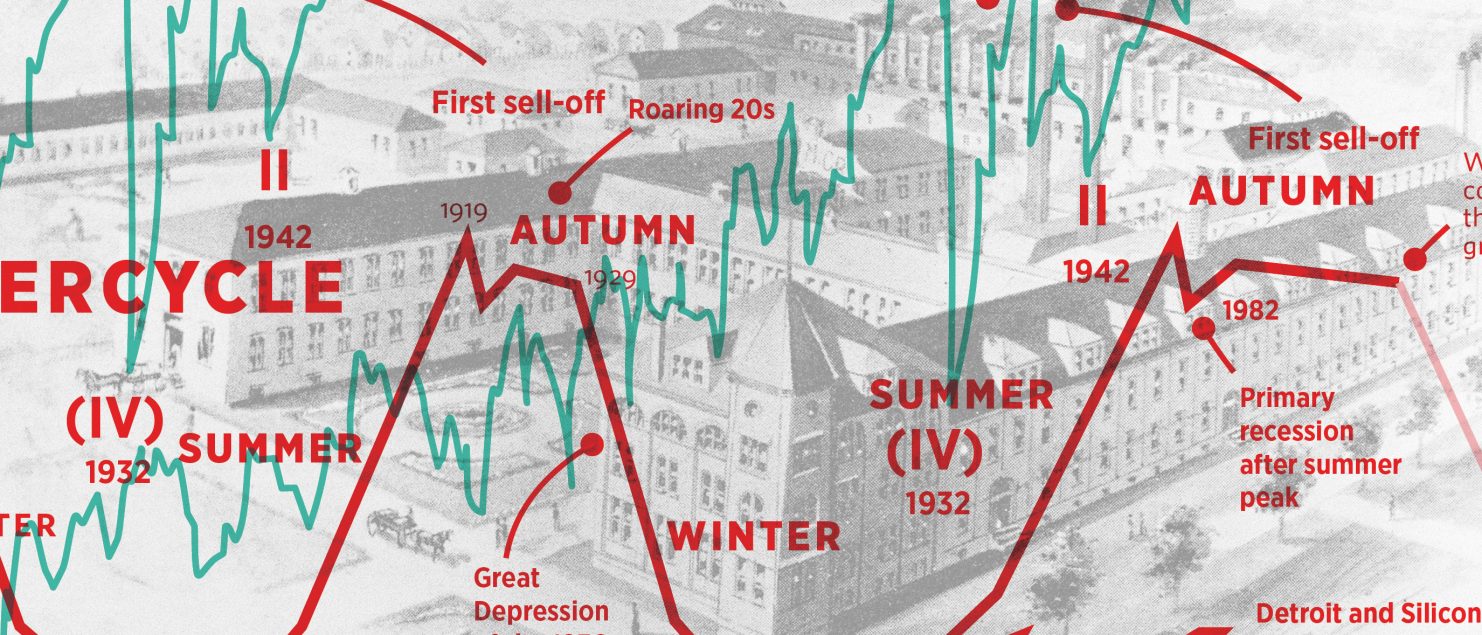

In February, I traveled from my home town of Toronto to Dayton to engage in field research for my Strategic Foresight and Innovation MDes project on industrial clusters and historical cycles of innovation (complex but involving Kondratieff and Schumpeter waves that look to the past and anticipate the future). Dayton was the U.S. home of my advisor, Dr. Peter Jones, who felt a study excursion to an American city that experienced a dramatic economic rise and fall could offer useful lessons for cluster development. Peter had called Dayton the Silicon Valley of the machine age, and I was curious to see if that was supported by history and what it meant for the next post-industrial age — an era that promises the fruition of a raft of presently-dormant scientific and digital revolutions, sometimes known as Industry X.O or Industry 4.0.

Starting off as a city of trading, Dayton became a place of small-scale manufacturing, eventually known as “the city of a thousand factories.” The Dayton of that era has indeed been described as a proto-Silicon Valley of mechanical engineering know-how with the capital to support a whole class of inventors and thinkers. In American Factory, Chairman Cao Dewang of Fuyao Glass America tours Dayton’s Carillon Historical Park, remarking how built-up early and mid-20th century was. I took the same tour in February, and surveyed the sheer presence of opportunities that the Dayton of that age provided, in cars, refrigeration, weight scales, electrical appliances, and countless other things that needed manufacturing — work that was often detailed and skillful.

By 1900, Dayton held more patents per capita than any other U.S. city. Dayton Historian Mark Bernstein notes that “by then, imagination was the city’s leading industry and its most significant export”.¹ As the U.S. economy took off after World War II, Dayton was home to the largest number of General Motors employees outside of Michigan. Its entrepreneurial climate nurtured inventions of all kinds, and like the Silicon Valley of the past few decades, innovation attracted more innovation. The Wright brothers and inventor extraordinaire Charles Kettering — who banished the hand crank for automobiles when he developed the self-starter — socialized together and traded ideas at the Engineers Club in downtown Dayton, just a block or two away from the Marriott where I stayed.

The National Cash Register Company and John Patterson

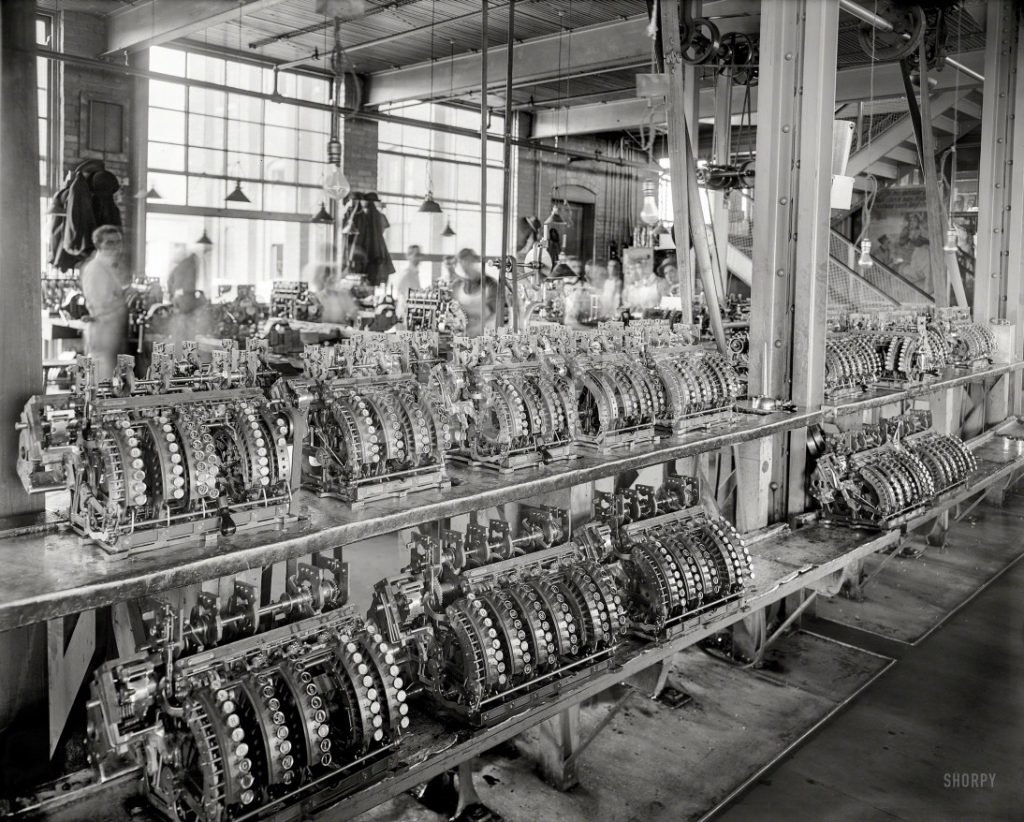

Kettering got his start at NCR, the industrial jewel of Dayton. John H. Patterson founded the National Cash Register Company, which by 1911, enjoyed a market share of 95 percent of the world’s cash registers. Rows of them can be seen at Carillon Historical Park, a riot of Victorian and Edwardian detail stamped into each example. This extraordinary market dominance was achieved by harnessing the scale advantages of selling and manufacturing the type of business machines that were transforming the practice of retail, while introducing a host of innovations across the entire range of business activities in manufacturing, marketing, and corporate leadership that forever changed the business landscape.² Patterson’s intense interest in building efficient organizations was coupled with an equally intense vigor for civic engagement, and its importance should not be glossed over by today’s businesses that wish to be leaders in their industry.

A dramatic example of this was Patterson’s application of scientific management to local government, tested out in the aftermath of the disastrous 1913 flood which destroyed much of downtown Dayton. NCR put out a call for the nation’s best minds to find a solution to Dayton’s flooding problem once and for all. The great minds answered the call, and succeeded in turning one of the most flood-prone areas on the planet into one of the least. In parallel with civic engagement, Patterson believed that better working conditions in the factory returned more in productivity and quality than the prevailing idea of a mass of workers that could be shunted in to replace staff who could just as easily be discarded. He created a kind of welfare program that focused on engendering self-respect, a broad self-interest in the world beyond work, and stimulated ambition.³ There seems to be a lesson here for present-day factories of the sort presided over by Chairman Cao Dewang that employs thousands of strained, dissatisfied workers. That the Fuyao Glass America story takes place in Dayton is a forceful reminder for me of all the good that has passed, and that the relative wages and aspirations of NCR-era Dayton will be wickedly difficult to claw back.

Roots of decline

The second half-century of NCR is a lesson in missed opportunities. In the 1930s, the company sensed electronics would one day become important to the development of the industry. For a time, NCR was a pioneer in computational research, but after World War II, the pent-up demand for NCR’s more traditional mechanical products caused management to ignore the opportunity to define the strategic direction for the digital computer. NCR continued into the 1950s and ’60s with a culture, leadership and operating methods that had not changed in decades. The idea that electronics could lead a transformation in the development of business machines was little noted by NCR executives in their leisurely approach to product development throughout the era.

If little organizational capital was allocated to an electronic future, a tremendous amount of capital was instead built into a vastly complex manufacturing enterprise devoted to the highly-integrated production of machine parts that employed thousands of workers. In the early 1960s, 2000 research and development staff worked in Dayton, their efforts constrained to working in the mechanical-centered status-quo.⁴ By the mid-1960s, NCR’s manufacturing and executive groupthink was a handicap, attended by increasing costs and inflexibility. Its core mechanical competencies became its core rigidities. I couldn’t help but sense a rigidity in some of the real-life characters of American Factory, who longed for the not-so distant past of $35-an-hour G.M. factory life, and now had to be content with less than half those wages. Couldn’t the workers themselves, the union that wants to represent them or the factory management find a better model that’s better than zero-sum?

Brush with destruction

Turning back to the NCR of the late 1960s, we find the technology’s relationship with the market becoming tenuous. During the 1960s, big department stores began to experiment with the new world of digital point-of-sale, but NCR struggled to make sense of the opportunity. By the end of the ’60s, NCR’s internal resources were strained, margins were squeezed and costs rose. The company barely broke even in 1971, and by then would drop to third place in the point-of-sale market. NCR would soon determine that as a part of their new longer-term strategy in the electronic era, it would have to make wrenching changes that would include letting Dayton’s operations dwindle away — and build up elsewhere.⁵

Many in Dayton would bitterly remember that NCR’s C.E.O. had shook off several invitations from

Ohio’s governor over two years to discuss the firm’s needs and desires in the region.

NCR would emerged from the 1970s as an electronics company, before it was too late. New leadership had recognized the need for its little-recognized dynamic capabilities to be harnessed in breaking from the limitations of manufacturing. But NCR’s world headquarters would close in 2009, moving to the Atlanta area. Many in Dayton would bitterly remember that NCR’s C.E.O. had shook off several invitations from Ohio’s governor over two years to discuss the firm’s needs and desires in the region. The C.E.O. countered that the firm found it difficult to get people to live, work and travel to Dayton.⁶ Other vital problems with the region had surfaced earlier. From the 1980s on, Dayton’s dependence on traditional manufacturing that emphasized machining and assembly line work put it at a competitive disadvantage as growing international trade and dramatically reduced transportation costs allowed for the global dispersion of factory work. It was part of a larger and slowly-moving decline of old industrial districts which saw their innovation and economic life erode, while other regions throughout the world emerged as new centres of invention.

A better model of innovation for Dayton: The Wright Brothers Institute

Regions that do well in scientific research do not always exhibit commercial success. Many mid-20th century leading-edge technology companies ran expensive research laboratories, engaging in projects that often didn’t develop into successful commercial products.⁷ In past decades, scientific research and development capabilities at Dayton’s Air Force Research Laboratory remained strong, with a largely civilian workforce of 21,000 creative minds. But the result of all this research could not bring about the vibrant commercial possibilities comparable to the culture of innovation in the golden era of Dayton.

In the last couple of years, however, a new culture of innovation has been awakened at Dayton’s Wright Brothers Institute (WBI). While walking through downtown Dayton carrying my take-out lunch from Smokin’ Bar-B-Que, I passed in front of the building that houses WBI (Tim Kambitsch of Dayton Metro Library had pointed the address out to me as he hosted me on my first evening in the city). Deciding to walk in in spite of my uncertainty of entering a building that is shared by the Air Force base, I got to see my first innovation hub up close. Upon entering the busy space, I boldly asked to be pointed to the head of the works, and was shown to Jim Masonbrink, Director of the Small Business Hub for WBI. Jim graciously chatted with me for a few minutes about what they were up to, pointing out infographic posters arrayed throughout the area that explains WBI’s successes in short phrases and figures.

In it’s initial phase of operations, WBI assessed why so little technology from laboratories and the region as a whole made it to commercial markets. They concluded that a lack of a strong integrated commercialization process sunk the promise of developing technology. “Solutions looking for a problem,” was frequently cited by technology developers. WBI partnered with The Stanford Research Institute in California to create a high-performing technology commercialization model that promised a better success rate. This commercialization concept ultimately yielded a variety of start-up businesses and new product lines unique to the State of Ohio. Rather than expecting entrepreneurs to “go it alone” or to mimic Silicon Valley practices, WBI’s model provides a balance between the agile flexibility needed to start a new venture with the structure that matches Midwestern values and risk tolerance.

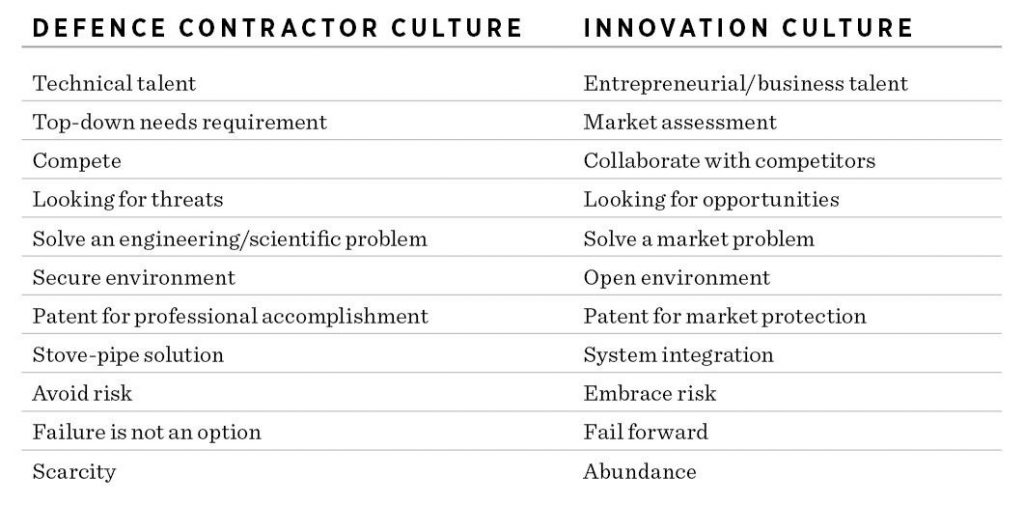

This new innovation model assumes that buyers do not care a great deal about technology but instead care about what value it can bring to them. Start-ups that demonstrate a strong market pull, the right technology and a unique value proposition allow for rapid capitalization. Additionally, constant refinement and iteration is considered critical components to success, allowing for modification of a product or service during the development of the business. Feedback from user groups, technical experts and business professionals can then be incorporated iteratively so that the product can get to market faster, and with fewer pitfalls. An interesting analysis compared Dayton’s then-current Defence Contractor mindset to the mindset of an innovation culture.⁸

WBI is one of a number of partnerships that have supported Ohio’s recent surge in homegrown start-ups. If quality of life where one works is considered important for regional success, many are seeing this ingredient in Ohio — contrary to the opinion held by NCR’s chief executive upon leaving Dayton, and, I believe, in opposition to the nature of work that has been instituted by the Chairman of Fuyao Glass America in American Factory. In the Forbes article “Why Ohio Is The Best State In America To Launch A Start-Up”, Peter Taylor writes, “Manhattan has the nightlife. San Francisco has the lifestyle. But Ohio has both for a fraction of the price”. Start-up costs such as overhead are far less, allowing the investment dollar to count for more.⁹ If a region like Ohio can establish the basis for a healthy industrial cluster that creates value for the world, the economic power, efficiency and focus of this cluster can offset mounting pressures for firms to relocate abroad.

The case study of Dayton and NCR offers up factors that can be read as signposts of warning for a developing cluster. The main lesson is that attitudes and business models that once made a firm or industrial cluster thrive in its early stage could calcify into inertia if comprehensive problem solving at the firm and cluster level isn’t embraced with better models for innovation and commercialization. But we can also see that more thoughtful business models, different from that of Silicon Valley in having been adapted for an Ohio way of life, can make Dayton ready for the road ahead. I hope to visit Dayton within the next decade and find that workers and business owners have found a new paradigm for an industrial age that can be a model for many regions just like it.

My Masters Research Project on learning from historical cycles of innovation can be found here:

http://openresearch.ocadu.ca/id/eprint/2548/

Bernstein, M. (1996). Grand eccentrics: Turning the century: dayton and the inventing of America. Wilmington: Orange Frazer Press.

Friedman, W. A. (1998, Winter). John H. Patterson and the sales strategy of the National Cash Register Company, 1884 to 1922. The Business History Review, Volume 72, №4, pp. 552–58. Retrieved from https://www-jstor-org.ocadu.idm.oclc.org/stable/pdf/3116622.pdf?refreqid=search%3A06e10dafb24eb5575eb56f22fb0c8d5e

Bernstein, M. (1996). Grand eccentrics: Turning the century: Dayton and the inventing of America. Wilmington: Orange Frazer Press.

Rosenbloom, R. (2000, October–November). Leadership, capabilities, and technological change: the transformation of NCR in the electronic era. Strategic Management Journal, Volume 21, №10/11.

Rosenbloom, R. (2000, October–November). Leadership, capabilities, and technological change: the transformation of NCR in the electronic era. Strategic Management Journal, Volume 21, №10/11.

Barry, D. (2010) In a Company’s Hometown, the Emptiness Echoes. New York Times, January 24.

McCraw, T. (2000). American business, 1920–2000: How it worked. Wheeling: Harlan Davidson, Ltd.

Wright Brothers Institute. (2018).

Taylor, P. (2017, February 20). Why Ohio is the best state in America to launch a start up. Forbes Magazine. Retrieved from https://www.forbes.com/sites/petertaylor/2017/02/20/why-ohio-is-the-best-state-in-america-to-launch-a-start-up/#1e88d211d948